Colonialism, at its core, represents the exploitation of a foreign group’s people and resources. This exploitation manifests through various mechanisms, including political, economic, and social control, designed to benefit the colonizing power. As the Collins English Dictionary states, colonialism is “the practice by which a powerful country directly controls another country or area and establishes its own trade and society there.” This definition highlights the inherent power imbalance at the heart of colonial relationships. Colonizers maintain a monopoly on political power, shaping legal systems, governance structures, and social hierarchies to serve their interests. Colonialism can manifest as settler colonialism, a specific form where large-scale immigration of settlers leads to the displacement and dispossession of Indigenous populations. Settler colonialism encompasses the invasion and occupation of territory by colonial settlers, reshaping the demographic and cultural landscape of the colonized land.

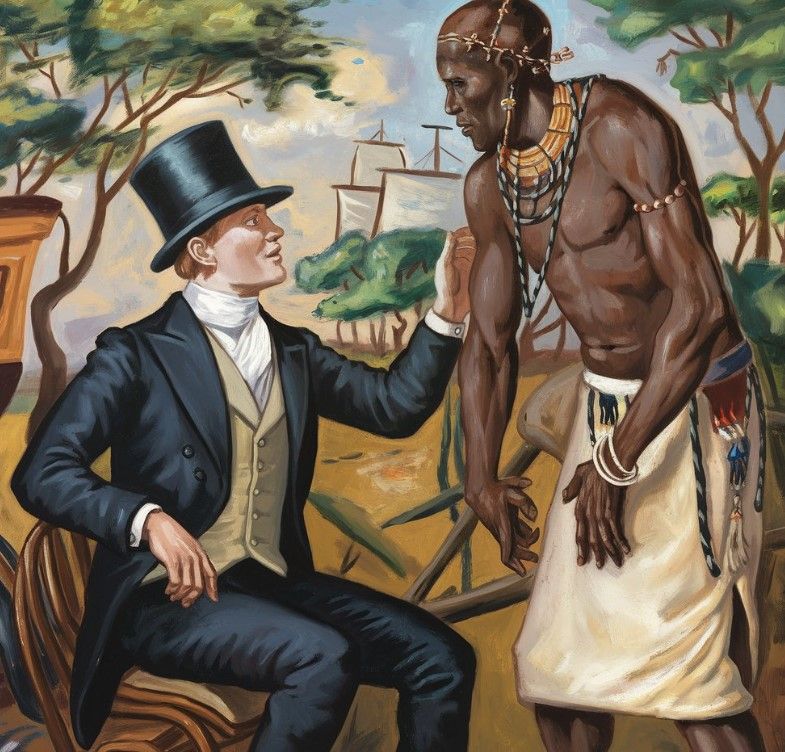

The historical trajectory of colonialism spans centuries, with roots tracing back to antiquity. The etymology of colonialism traces back to the Latin word “Colonus.” Within the Roman Empire, “Colonus” designated tenant farmers, foreshadowing the concept of land appropriation and control that would characterize later forms of colonialism. Early usage of the word colonialism related to plantations, reflecting the economic motivations driving colonial expansion. European colonialism, particularly during the early modern period, utilized mercantilism, an economic system that prioritized accumulating wealth through trade and resource extraction. Colonies served as sources of raw materials and markets for finished goods, fueling the economic growth of European powers. Colonialism found justification in beliefs of a civilizing mission, a paternalistic ideology used to rationalize the subjugation and exploitation of non-European peoples. This self-serving narrative cast colonizers as benevolent actors bringing progress and enlightenment to supposedly backward societies.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy employs the term colonialism in its discussions of political philosophy, recognizing the concept’s enduring relevance in understanding global power dynamics. It acknowledges the multifaceted nature of colonialism, encompassing various forms such as exploitation colonialism, which centers on the exploitation of resources or labor; surrogate colonialism, comprising a settlement project backed by a colonial power; and internal colonialism, representing a concept of unequal structural power within a nation-state.

Throughout history, numerous empires and nations engaged in colonial practices. Phoenicians, Greeks, and Romans established colonies throughout antiquity, extending their influence across the Mediterranean and beyond. Vikings formed colonies in Britain, Ireland, Iceland, and other regions, demonstrating the expansive reach of early colonial ventures. European Crusaders instituted colonial regimes in the Levant during the Middle Ages, establishing a precedent for later European colonial expansion. The Ottoman Empire’s capture of Constantinople in 1453 shifted the balance of power in the Eastern Mediterranean and impacted trade routes, influencing European exploration and expansion.

The Age of Exploration marked a pivotal moment in the history of colonialism. The Crown of Castile made contact with the Americas in 1492, initiating a period of profound transformation for both Europe and the Americas. Oriental land and sea routes, vital for trade in valuable goods like spices, converged at ports in the Crimea, Trebizond, Constantinople, and other locations. Venice triumphed over Genoa in a struggle for commercial dominance, securing control over Oriental trade. Venice held a near-complete monopoly on spices, including pepper, nutmeg, cloves, and cinnamon, highly sought-after commodities in European markets. Portugal and Spain divided the non-Christian world between themselves through the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. This treaty delineated a line of demarcation, granting Portugal control over territories east of the line and Spain control over territories west of the line. Portuguese rule in territories like Brazil stemmed from the Treaty of Tordesillas, discoveries, and papal approval, solidifying their claim to vast swathes of land. Almeida controlled strategic points in eastern Africa and India, establishing Portuguese presence in key trading regions. Albuquerque took Goa, Malacca, and Hormuz, further expanding Portuguese control over maritime trade routes. Spaniards inhabited West Indian islands, establishing colonial settlements and exploiting Indigenous labor. Balboa journeyed to the Pacific in 1513, opening up new avenues for Spanish exploration and conquest. Cortés ventured into Mexico, leading to the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. The Pizarro brothers ventured into the Inca Empire, culminating in its conquest and the establishment of Spanish colonial rule. The Spanish crown established the House of Trade (Casa de Contratación) in 1503 to regulate trade and administer colonial affairs.

The rise of other European powers challenged Spanish and Portuguese dominance. The Dutch undermined Spanish authority in the 17th century, establishing their own colonial empire. The Dutch navigated across all known oceans, demonstrating their maritime prowess and expanding their global reach. The Dutch States-General officially established the United East India Company in 1602, granting it exclusive navigational rights and extensive powers in the East Indies. Jan Pieterszoon Coen served as governor general of the Dutch East Indies, overseeing the expansion of Dutch colonial control in the region.

Colonialism, in its essence, signifies “control by one power over a dependent area or people.” It arises when one nation subjugates another, imposing its political, economic, and cultural systems on the colonized population. Colonialism and imperialism share a close connection, often used interchangeably, but with subtle distinctions. Imperialism constitutes the policy of exerting power to dominate another nation, while colonialism refers to the specific practice of establishing and maintaining colonies. Ancient Greece, Rome, Egypt, and Phoenicia engaged in colonialism, expanding their territorial boundaries and founding colonies to secure resources, establish trade routes, and exert political influence. Greek city-states created colonies throughout the Mediterranean, establishing new settlements and extending their cultural and political reach. The establishment of a new colony often relied on the financial support of a wealthy benefactor, highlighting the economic dimensions of colonial ventures.

Portugal’s pursuit of new trade routes spurred its exploration and expansion. Portuguese explorers seized Ceuta in 1415, marking an early step in their colonial endeavors. The Portuguese conquered and settled Madeira and Cape Verde, establishing their presence in the Atlantic. Columbus’s arrival in the Bahamas in 1492, under the Spanish flag, marked a turning point in global history, leading to the widespread colonization of the Americas. Spain and Portugal appropriated Indigenous lands, displacing and exploiting native populations. England, the Netherlands, France, and Germany initiated empire building, joining the race for colonial possessions. Bandeirantes in Brazil undertook expeditions into the interior, aiming to capture and enslave Native people. European slavers engaged in the Atlantic slave trade, forcibly transporting millions of Africans to the Americas for enslaved labor. The U.S. expanded its territorial reach westward, displacing and subjugating Indigenous populations. European nations started seizing control of African nations in the late 19th century, culminating in the Scramble for Africa. The British Empire, at its height, possessed territories across all time zones, illustrating the vast scale of colonial expansion.

Colonial powers rationalized their acts of conquest through various ideological frameworks. Conquering nations portrayed themselves as civilizing forces, bringing progress and enlightenment to supposedly backward societies. Church leaders supported and actively participated in the acquisition of foreign lands, providing religious justification for colonial expansion. Papal bulls, specifically the Doctrine of Discovery, declared colonization essential for spreading Christianity and legitimized the seizure of non-Christian lands. Resistance to colonial rule manifested in various forms, including armed uprisings and cultural resistance. The Pueblo Rebellion toppled Spanish rule in New Mexico in 1680, demonstrating the power of Indigenous resistance. The slave revolt in Haiti in 1791 evolved into a full-scale revolution, resulting in the establishment of the first independent Black republic in the Western Hemisphere. Ethiopia, despite facing colonial pressures, maintained its independence throughout much of the colonial era.

While colonial governments made investments in infrastructure and trade, and facilitated the spread of knowledge, these actions primarily served the interests of the colonizing power. Colonialism produced a legacy of environmental damage, disease, political instability, international rivalries, and human rights violations. Decolonization, the process by which colonies gained independence, resulted in the emergence of new nation-states in the 20th century. However, colonialism continues to exert a lasting influence on contemporary issues, shaping political, economic, and social dynamics in former colonies. Some academics apply the term neocolonialism to describe the continuing influence of former colonial powers in the affairs of independent nations.